July 2021

7/13/2021 | BY Cheryl R. Lawing, MD

Tips for Caring for the Child with Severely Involved Neuromuscular Disease

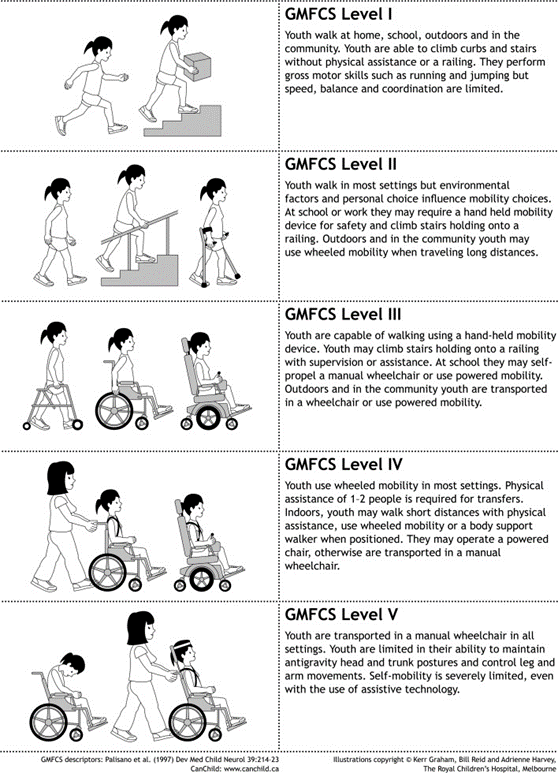

It is important to have a good understanding of the cognitive and functional level of the patient. The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) can be used to classify a patient’s functional level and is an important tool to help us make predictions about a child’s future function. (See below figure)

While many children with severe neuromuscular disease will have concomitant global developmental delay, it is important to understand the level of cognitive involvement for the child. The more severely delayed child may better tolerate a custom molded wheelchair and worse pelvic obliquity, while a child able to communicate verbally or with keyboard or assistive device will have a greater health related quality of life impact as sitting balance deteriorates that may push towards intervention.

Mobility can be assessed by asking the parent: If you put him/her in the middle of the living room floor, what does he/she do? This gives insight into a child’s desire/capability for mobility such as crawling, rolling, or knee walking.

2. Evaluate the whole child

Unlike many orthopaedic patients, where we enjoy the luxury of focusing on our small niche, it is essential that we evaluate the whole child and keep in mind the other co-morbidities that commonly exist. While many families may not be able to tell you detailed medical diagnoses, you can gain good insight by simply asking “what other types of doctors does he/she see.”

Pay attention to nutritional status. Spastic muscles are constantly active and poor nutrition is not uncommon. Additionally, many of these children have impaired swallowing, reflux, and gastric motility issues. Hyper-salivation is uncommon as well and aspiration pneumonia can be a major concern and potential source of demise for these patients. Just because a child does not currently have a G-tube does not mean they don’t need one. Especially when considering major surgery like hip or spine, swallow studies and GI evaluation are very helpful.

Seizures are common in these children and certain antiepileptic medications, such as valproate, can increase bleeding risks perioperatively. Co-management with the child’s neurologist to potential change away from these drugs may be necessary before surgery. There has been concern that the seizure threshold is lower post-operatively in these children following spine fusion where MEPs are monitored. Fortunately, it appears that MEPs can still be monitored safely without an increased risk for seizures (Shrader, POSNA 2021 Annual Meeting)

3. Differentiate spasticity from contractures

The level of tightness in a muscle that is first encountered, but can be overcome, is documented as R1 and indicates the level of spasticity of a muscle. The contracture of a joint that cannot be overcome is documented as R2 and indicates a true joint contracture. As surgeons, we primarily deal with R2. However, spasticity can play a major role in limiting function for these children and a multidisciplinary team approach is important. Physiatry can help with tone management through systemic medication such as baclofen and tizanidine, or assisting with evaluation for more localized management with intrathecal baclofen pumps or selective dorsal rhizotomy. Knowing the limitations that we as surgeons have to only treat the downstream effect of the underlying neurologic cause for these children’s contractures and limitations is essential. These are not children we should be treating in isolation. Rather, these complicated children require a team approach.

4. Understand the family’s goals and struggles

The families of these children deal with a great many more struggles than parents of typically developing children. In some ways, they go through a prolonged sense of mourning as their child grows and they gain further understanding of their child’s limitations. They see their friend’s and relative’s children gaining exciting new milestones and struggle to see that their child maintains the developmental level of a baby or very young child. It is our role as physicians to provide a realistic education on the expectations for their child’s future in a kind and compassionate way. It can be devastating for a family to be matter-of-factly told that their child will never walk. We absolutely should not create false hope, but we must understand that these parents go through a grieving process throughout their child’s life as they better understand his/her limitations. Helping parents achieve this understanding is realistically a slow process gained gradually after a multitude of encounters. We may get frustrated at having to repeat over and over what feels like the same thing, but this is overwhelming information for these families that takes time to process. I like to use the expression “I always like for children to prove me wrong, but based on the medical community’s experiences with children having similar conditions, I would expect that he/she won’t be able to walk.”

It is our role to educate these families in a loving manner. It is difficult for non-medical people to understand that normalization of anatomy does not change the inability of the brain’s motor pathway to coordinate activities.

Listen to these families and find out what is important to them. A severely involved GMFCS V patient does not necessarily need braces to prevent foot contractures. To some families, maintaining the ability to wear shoes is important from a social standpoint or protection against cold climates. To other families, this is extra expense, time, and burden of care for something that, in the eyes of these parents, provides no functional impact for the child. Standers provide great enjoyment for some patients, but for others it means expensive therapy co-pays and parents struggling to take off work to get the child to therapy. Not all children need lifelong therapy once initial goals are met and plateaued. Care of these children involves shared decision making and we as physicians need to listen to the families.

5. Walking is not the most important thing

Families get hung up on walking as the end-all-be-all and it is important that we help them understand that there are far more important things for their child. First and foremost, we must not forget social and communicative development. While therapies have their role, we should also be mindful of the social and financial burden they place on a family. A child constantly being taken out of class, away from his/her peers, to go to school therapy may be losing more in terms of social interaction and development than what is being gained by spending a short duration in a stander.

Mobility is very important, but mobility does not necessarily mean walking. This can be a very difficult thing for families to understand and no doubt takes a great deal of time to understand. We want to give younger children every opportunity to develop what they can from a functional standpoint, but we should also be helping families understand that as adults, wheelchairs and assistive devices are often the most efficient means of being