April 2016

4/25/2016 | BY Richard McCarthy, MD

Ethical Guidelines

Ethics are intimately related to the practice of medicine and affect many of our daily decisions linked to how and when we care for individuals. From an early age we are raised to differentiate between right and wrong. These principles are reinforced and honed to a sharp edge by parents, schools, churches, military and society through laws, rules and guidelines. We begin our lives in Medicine with an oath to maintain high ethical standards filled with “warmth, sympathy, and understanding” and applying to the sick “all measures which are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism”* (modern Hippocratic oath written by Louis Lasagna, Dean of Tufts University of Medicine, 1964).

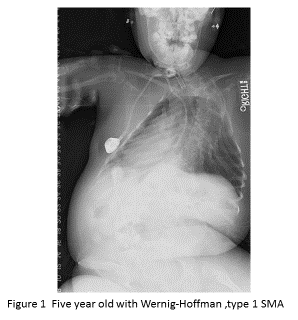

Our lofty ideals are often challenged by demands on our time, lack of funds, institutional mandates and at times, fatigue. We all should endeavor to do our best for our patients within the systems where we work, at all times. But what can we do when what is “right” is unclear and doing our “best” is seemingly doing nothing? We present a case for consideration that poses a dilemma in decision making. A five year old child with a rare form of spinal muscular atrophy presents for spinal surgery. The child is known to have Werdnig-Hoffman Disease which is fatal in all cases before age five. The neurologic impairment is usually profound and in this case the child had no purposeful movement. She could blink her eyes but that, too, was not purposeful. The child was alive because the mother had insisted upon a tracheotomy and placement on a ventilator 24/7. The State Medicaid supplied nursing coverage around the clock. The mother was requesting spinal surgery for her significant deformity (Figure 1).

The situation leaves most of us in a quandary. Do we prolong this child’s life or let her die a natural pulmonary death when we have the tools to prolong life?

What guidelines can we follow in such a scenario? There are accepted principles of moral reasoning that can and should guide our thought processes:

- Principle of Non-maleficence requires a surgeon to avoid harming a patient.

- Principle of Justice implies that the treatment must be fair to the patient and/or society from the stand point of benefits, risks and cost.

- Principle of Autonomy requires respect for the individual and their right to be properly informed so as to make a choice that’s right for them.

- Principle of Beneficence requires the surgeon to help the patient.

These well-established principles become blurred when discussing terminal illnesses in children but they may help us to sort through what was done in this case.

The surgeon was perplexed by the mother’s request and sought the counsel of the Children’s Hospital Ethics Committee which reviewed the case, interviewed all the parties involved, and deliberated for over three hours. No decision could be reached and the surgeon was left to decide on his own. He decided after much reflection to operate.

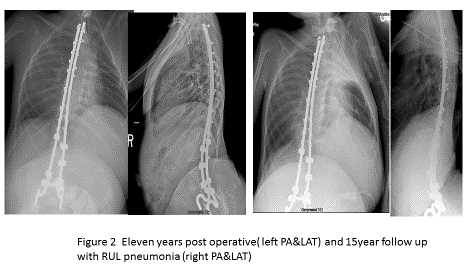

The child recovered quickly and uneventfully from insertion of a Luque growing rod system. Her x-rays at her 11 year follow up visit showed continued correction and growth without change in her social or physical condition. The same condition was noted at her 15 year post-op, except for a pneumonia, which was treated without event (Figure 2).

Using our principles of moral reasoning, what conclusion can we draw from this situation?

Question 1: Was the patient harmed by the treatment? Answer: Not physiologically.

Question 2: Was this fair to the patient?

Answer: Unknown, the natural course of death was averted; her life was prolonged without adding anything to the quality of her life.

Question 3: Was the treatment fair to society?

Answer: Most medical economists would say no, and probably with emphasis, because of the profound financial outlay for ventilatory and nursing support in the face of a hopeless prognosis.

Question 4: Was the individual given proper respect in the decision process?

Answer: Totally unknown; the daily suffering of the child remains inside and a parent’s decision is very complex and conflicted. The easiest decision here is no decision and continue to allow the State to support the non-decision.

Question 5: Was the patient helped?

Answer: Questionable, since sometimes the most compassionate thing we do as physicians is allow patients to die with compassion (not assisted).

These dilemmas will continue to confront and challenge us. More and more we are asked to weigh in on the cost/benefit/risk triangle when benefits are not as yet well established. Often we are asked by third party payers to prove the benefit to patients and society regarding the work we do. Our challenge is to fill in this void in our medical knowledge in order to aid our ability to treat patients. The SPORT studies on spine care in North America and the National Health Study on magnetic rods in the United Kingdom are examples of ways to fill the knowledge gap and enhance patient care

If we as practitioners don’t continue to prove the benefit, then medical payor systems could very likely cut back paying for unproven treatments.

When faced with these difficult ethical decisions seek advice from colleagues, from Ethics Panels, from Medical/Surgical Societies and mentors. It remains critical however, that the proper and best care of the patient remain primary as our goal at all times.