Study Guide

Spondyloepiphyseal Dysplasia Congenita and Tarda

Key Points:

SED Congenita- Usually caused by a spontaneous (but sometimes autosomal dominant) mutation in COL2A1 gene on Chromosome 12, which causes an alteration in the length of Type 2 collagen.

- Patients are characterized by short stature (max ~4 feet) with key spine findings including scoliosis, platyspondyly, increased lumbar lordosis, and atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia or os odontoideum.

- Flexion-extension C-spine x-rays should be ordered every 3 years or before anesthesia in presence of odontoid hypoplasia or os odontoideum.

- Nearly all patients exhibit coxa vara of the hips with increasing degrees of varus accompanied by substantial hip flexion contracture.

- Proximal femur valgus osteotomy, joint contracture releases, and spinal fusion may be necessary orthopedic treatments.

- Distinguised from SED congenita as characteristic features are milder and identified later in childhood.

- Usually caused by X-linked mutation in SEDL or TRAPPC2, which encode for proteins involved in cellular transport, but autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant presentations are also seen

- Patients typically present with hip pain and can be confused as having bilateral Perthes disease. Patients often go on to require total hip arthroplasty.

Description:

SED CongenitaWith an estimated prevalence of 3 to 4 per 1 million people, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (SED) congenita is a rare condition. Key features include significant spinal and epiphyseal involvement, which results in a short trunk and neck. While most patients have a new spontaneous mutation, inheritance of SED congenita has also been observed to sometimes follow an autosomal dominant pattern.

SED Tarda

SED tarda is a milder form of SED, often not identified clinically at birth, with key manifestations becoming subtly apparent at approximately 4 years old. The spine and only the larger joints are affected. Height is minimally affected, which also delays diagnosis as patients can be 5 feet or taller. Many patients present with complaints of hip pain. The most common form of inheritance is X-linked recessive.

Epidemiology:

Clinical Findings:

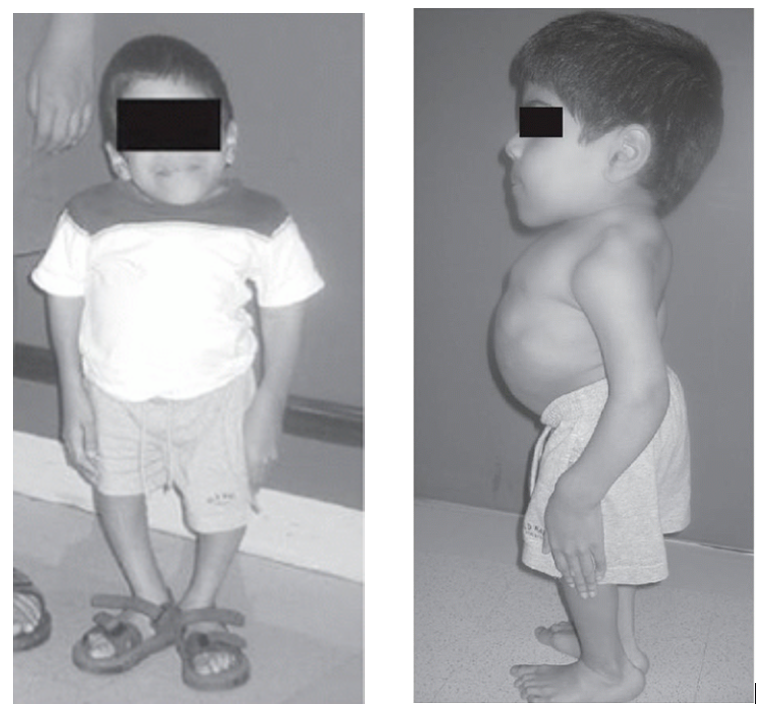

SED CongenitaThere are many common clinical findings in these patients. First, short stature is present along with a short neck, barrel chest, and increased lumbar lordosis (Figure 1). Respiratory problems can occur in infants due to a small thorax.

The extremities are also short, with angular deformities of the extremities common. Genu valgum and coxa vara are frequently present, which often results in a waddling gait. The degree of coxa vara has been thought to be the best marker for the variable severity of the disease. If the varus is severe, it is often accompanied by significant hip flexion contractures, causing patients to walk with the trunk and head held back to compensate. Clubfoot deformity has also been described in children with SED.

Figure 1 (left): 12-year-old male exhibiting typical features of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita including short stature, short neck, barrel chest, increased lumbar lordosis, and hip flexion contracture (Reproduced from Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 8th ed)

Figure 1 (left): 12-year-old male exhibiting typical features of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita including short stature, short neck, barrel chest, increased lumbar lordosis, and hip flexion contracture (Reproduced from Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 8th ed)Facial abnormalities are common and include taut face, small mouth, and cleft palate. Patients also can have retinal detachment, cataracts, hearing difficulties, and hernias. Retinal detachment occurs primarily during the adolescent growth spurt requiring regular ophthalmologic examinations during this time period.

SED Tarda

The clinical manifestations of SED tarda are much milder than the congenita form. The earliest reported cases were recognized at age 4, although most patients present during middle childhood or adolescence. Presenting clinical findings primarily include hip pain with early arthrosis or short stature. Presentation for these patients is more subtle than that of patients with SED congenita.

Imaging Studies:

SED CongenitaA hallmark feature of this condition is a delay in appearance of the epiphyses due to a delay in ossification. This is commonly observed with the epiphysis of the femoral head not appearing until after age 5 or even much later. When ossification centers do appear radiographically, they are small and irregular in appearance (Figure 2). The proximal femur typically has a short neck with coxa vara. Often, the varus is progressive, and there may be progressive extrusion of the femoral head, which requires an arthrogram to show it clearly. Flaring of the distal femoral metaphyses is noted as well as genu valgum.

Figure 2 (left): Characteristic irregular epiphyses seen in a patient with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita along with flaring of the distal femoral metaphyses (Reproduced Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: A radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias. World Journal of Radiology 2014; 6(10): 808-25.)

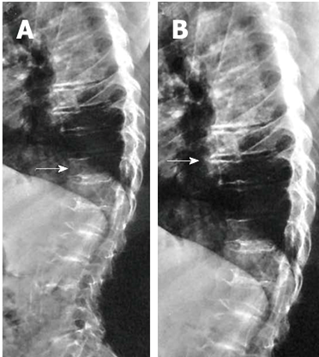

Figure 2 (left): Characteristic irregular epiphyses seen in a patient with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita along with flaring of the distal femoral metaphyses (Reproduced Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: A radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias. World Journal of Radiology 2014; 6(10): 808-25.)There is often odontoid hypoplasia or os odontoideum. Due to this, routine cervical spine films should be obtained at frequent intervals to assess for atlantoaxial instability. Lateral flexion-extension cervical radiographs should be obtained before anesthesia. Lateral radiographs of the thoracolumbar spine show platyspondyly with severely reduced disc spaces as patients mature (Figure 3). Patients with scoliosis and this condition have curves with a sharp angulation over only a few vertebrae.

Figure 3 (right): Lateral spine radiograph with characteristic platyspondyly and narrowing of disc spaces observed in patients with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita. (Reproduced Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: A radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias. World Journal of Radiology 2014; 6(10): 808-25.)

Figure 3 (right): Lateral spine radiograph with characteristic platyspondyly and narrowing of disc spaces observed in patients with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita. (Reproduced Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: A radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias. World Journal of Radiology 2014; 6(10): 808-25.)SED Tarda

SED Tarda radiographic findings also mainly involving the epiphysis like in SED congenita. Epiphyseal changes are most commonly seen in the hips and can be confused with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. The hips often present with coxa magna, flattening (Figure 4), and extrusion of the femoral head from the acetabulum. Other epiphyses can also be found to be involved, including the proximal humerus and the distal femurs. Spine manifestations include disc space narrowing and platyspondyly, but these along with other radiographic findings are subtler and present later compared to SED congenita. Mild to moderate scoliosis can develop in a small minority of patients.

Figure 4: Patient with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia tarda who has developed flattening of the femoral head along with premature degenerative changes. (Reproduced Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: A radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias. World Journal of Radiology 2014; 6(10): 808-25.)

Figure 4: Patient with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia tarda who has developed flattening of the femoral head along with premature degenerative changes. (Reproduced Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: A radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias. World Journal of Radiology 2014; 6(10): 808-25.)Treatment:

SED CongenitaOne of the biggest concerns with SED congenita is myelopathy due to cervical instability caused by os odontoideum, odontoid hypoplasia, or aplasia. Thorough neurological exams should be performed routinely. Instability can be present even in infancy and can present with respiratory insufficiency. Flexion-extension radiographs should be performed before anesthesia and approximately every three years if an upper cervical anomaly is identified. CT or MRI can be helpful if odontoid is difficult to visualize on radiograh. Patients often have congenital cervical stenosis as well, which can magnify the deleterious effects of cervical instability. Surgical treatment includes atlantoaxial fusion if myelopathy develops or if instability is greater than 8mm. If a fixed subluxation cannot be reduced, it may be necessary to perform a decompression of the atlas with fusion to the occiput. As the small bone size of neural arches in young patients precludes internal fixation, halo immobilization is often necessary in younger patients. Once patients are over 6 to 8 years, transarticular screw fixation can be considered.

Over 50% of patients with SED congenita can develop severe scoliosis, which can be treated with bracing below 40 degrees and fusion beyond 50 degrees. Low threshold exists for augmentation with halo traction if internal stabilization is complicated by severity of the curve or pedicle size. Additionally, anterior surgery can be considered in young patients less than 11 years old or for rigid curves.

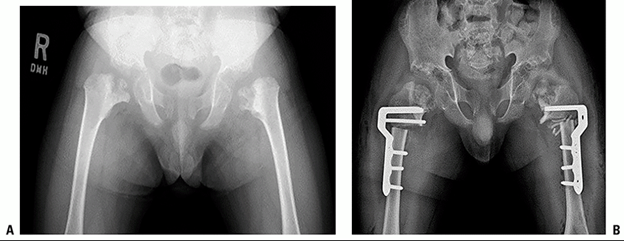

Proximal femoral osteotomies are indicated if the neck-shaft angle is <100 degrees, and it is helpful to correct flexion contractures, which are common, at the same time (Figure 5). If a patient is experiencing painful hinge abduction, a valgus osteotomy may improve symptoms. Knee alignment should also be assessed and corrected, through guided growth or osteotomies, if necessary. Foot deformities can usually be treated according to standard clubfoot principles. If the foot is stiff, an osteotomy or decancellation of the talus, calcaneus, and/or cuboid may be needed.

Figure 5: 7 year old with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita and characteristic severe coxa vara treated with proximal femoral valgus producing derotational osteotomy congenita (Reproduced from Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 8th ed)

Figure 5: 7 year old with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita and characteristic severe coxa vara treated with proximal femoral valgus producing derotational osteotomy congenita (Reproduced from Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 8th ed)SED Tarda

Pain and arthrosis from femoral head involvement in these patients often necessitate surgical intervention. Early surgical interventions can potentially be performed in an attempt to achieve concentric femoral head coverage in an effort to delay symptomatic arthritis; however, there are no adequate studies evaluating surgical interventions to delay or prevent hip arthritis in this patient population. Additionally, most of these patients end up undergoing total hip arthroplasty after skeletal maturity at an average age of 40.

Spinal manifestations are much less common in SED Tarda patients compared to congenita patients. Patients often will complain of back pain that does not require surgical intervention. Scoliosis can be present, and recommendations for treatment of these curves are similar to patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.

Complications:

Related Videos:

References:

- Anonymous. International nomenclature and classification of the osteochondrodysplasias (1997). International Working Group on Constitutional Diseases of Bone. American Journal of Medical Genetics 1998; 79(5): 376-82.

- Bassett GS. The osteochondrodysplasias. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, editors. Pediatric Orthopaedics. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. p. 203-49.

- Dahiya R, Cleveland S, Megerian CA. Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita associated with conductive hearing loss. Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal 2000; 79(3): 178-82.

- Hall CM, Elcioglu NH, Shaw DG. A distinct form of spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia with multiple dislocations. Journal of Medical Genetics 1998; 35(7): 566-72.

- Horan F, Beighton P. Orthopaedic problems in inherited skeletal disorders. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1982.

- Kornblum M, Stanitski DF. Spinal manifestations of skeletal dysplasias. Orthopedic Clinics of North America 1999; 30(3): 501-20, x.

- Nakamura K, Miyoshi K, Haga N, Kurokawa T. Risk factors of myelopathy at the atlantoaxial level in spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita. Archives of Orthopaedic & Trauma Surgery 1998; 117(8): 468-70.

- Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: A radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias. World Journal of Radiology 2014; 6(10): 808-25.

- Rimoin DL. Molecular defects in the chondrodysplasias. American Journal of Medical Genetics 1996; 63(1): 106-10.

- Sponseller PD, Ain MC. The Skeletal Dysplasias. In: Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 2014: 177-217.

- Sponseller PD, MacKenzie WG. The Skeletal Dysplasias. In: Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 2021: 233-237.

- Wynne-Davies R, Hall C. Two clinical variants of spondylo-epiphysial dysplasia congenita. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery -British Volume 1982; 64(4): 435-41.

Top Contributors:

Ravi Rajendra, MDRobert F. Murphy, MD

Maegen Wallace, MD