Study Guide

Congenital Vertical Talus

Key Points:

- Congenital vertical talus (CVT) is a rare foot condition resulting from a dorsal dislocation of the talonavicular joint with rigid hindfoot valgus and equinus

- The specific etiology of CVT is largely unknown but in approximately 60% of cases the condition occurs in combination with either neurologic conditions, certain genetic disorders, or known syndromes

- A minimally invasive surgical approach yields positive five-year outcomes

- Early surgical intervention is vital to successful correction and prevention of the consequences of a neglected vertical talus

Description:

Congenital vertical talus (CVT) is a rare, rigid foot condition that is characterized by a dorsal dislocation of the talonavicular joint with rigid hindfoot valgus and equinus. This structural deformity gives rise to a rocker bottom appearance to the plantar aspect of the midfoot. The diagnosis of congenital vertical talus can sometimes be missed due to similarities to other more benign pediatric foot conditions.Classification

The Coleman classification is the most widely used description classification for CVT, which describes two types. The first describes talonavicular dislocation and the second describes talonavicular dislocation with concomitant subluxation or dislocation of the cuboid on the calcaneus (Coleman, Stelling, and Jarett 1970). This classification, as well as others (Litchblau) tend to focus on the talonavicular dislocation occurring either with or without other abnormalities. Therefore, these classifications are solely descriptive with no guidance of treatment (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022; Miller and Dobbs 2015).

Epidemiology:

While the true incidence of CVT is unknown, its estimated prevalence is about 1 in 10,000 live births. Some suggest that this estimate is low and suggest a need for additional studies to help discern gender predilection and laterality (Miller and Dobbs 2015).Clinical Findings:

Physical ExaminationClinically, CVT has the distinct plantar surface convexity that results in a rocker-bottom appearance (Miller and Dobbs 2015; Mckie and Radomisli 2010). The hindfoot is noted to be in significant valgus and equinus with forefoot abduction and dorsiflexion (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022). Due to these positional characteristics, the dorsum of the foot typically has deep creases. A palpable gap may also be noted dorsally immediately above the talonavicular articulation. If the child is of walking age, significant callosities can occur along the plantar medial surface of the foot overlying the talar head, resulting in difficulty with shoe wear. An important key to the overall diagnosis of the foot is the remarked amount of clinical rigidity of the deformity, which helps to narrow the differential diagnosis (Miller and Dobbs 2015).

Because of the frequency of neurological conditions, genetic abnormalities, and associated syndromes, a comprehensive clinical examination is necessary to rule out any underlying anomaly. Motor function of the foot should be evaluated with focus on the great toe as well as the lesser toes. Patients with weakened or absent ability to move the toes typically have a vertical talus deformity that is more rigid, less responsive to treatment, and indicative of underlying neurologic or muscular anomaly (Miller and Dobbs 2015).

Calcaneovalgus foot should not be confused with CVT as it is immediately distinguished by its flexible nature, with hindfoot being positioned in dorsiflexion as opposed to equinus (Mckie and Radomisli 2010). Additionally, a child of walking age with a flat foot and heel cord contracture at first glance can be mistaken for CVT. However, the flat-footed child maintains flexibility with correction of hindfoot valgus via inversion of the foot and reconstitution of medial arch via toe walking (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022; Mckie and Radomisli 2010).

Associated Anatomy

The rocker bottom deformity and convex appearance of the plantar foot result from the vertical orientation of the talus causing substantial weakening and stretching of the deltoid ligament and plantar soft tissues including the spring ligament (Miller and Dobbs 2015; Mckie and Radomisli 2010). The hindfoot is found to be displaced posterolaterally in relation to the talus and in contact with the distal aspect of the fibula. The calcaneocuboid joint can show a variable degree of subluxation (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022). Additionally, the calcaneus is in marked equinus and valgus due to a contracted Achilles tendon and fibrotic subtalar and posterolateral tibiotalar joint capsules (Miller and Dobbs 2015). These abnormalities result in elongation of the medial column and relative shortening of the lateral column of the foot.

The midfoot and forefoot are dorsiflexed and abducted relative to the hindfoot secondary to the contracted extensors of the anterior compartment. The posterior tibial tendon and the peroneal tendons are found to be anteriorly subluxated; they function more as dorsiflexors than plantarflexors (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022; Miller and Dobbs 2015). Furthermore, the navicular is found to be hypoplastic and wedge-shaped, and it articulates dorsally and laterally with the flattened head of talus (Miller and Dobbs 2015).

Imaging Studies:

In the newborn, the diagnosis of CVT is challenging because only the ossific nuclei of the calcaneus, talus, metatarsals, and phalanges are visible radiographically. The cuboid ossific nucleus appears during the first month of life. The cuneiforms begin ossification at approximately three years, with the lateral cuneiform appearing first (Miller and Dobbs 2015; Mckie and Radomisli 2010). The navicular ossifies at approximately 3 years of age (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022).Standard radiographic evaluation of CVT includes an AP view and lateral view of the foot. In addition, lateral views taken in maximal dorsiflexion and maximal plantar flexion should be obtained (Miller and Dobbs 2015; Mckie and Radomisli 2010). Standing views can also be obtained in older children.

On AP projection, the talocalcaneal (Kite) angle will show a value greater than 40 degrees consistent with hindfoot valgus (Mckie and Radomisli 2010). On the lateral projection, the talus appears almost vertical with near parallel orientation to the tibial shaft. If the navicular is unossified, its position can be inferred from the direction of the metatarsals and any ossified cuneiforms. The navicular will always reveal dorsal dislocation relative to the talus (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022; Miller and Dobbs 2015). The long axis of the talus will additionally be vertical in relation to the first metatarsal. This will yield a high talocalcaneal angle (Miller and Dobbs 2015). The calcaneus will be noted to be in fixed equinus, which can be further demonstrated via a lateral maximal dorsiflexion radiograph.

A maximal plantar flexion lateral view is necessary to differentiate CVT from a condition known as oblique talus. In oblique talus, the talonavicular joint will reduce with the foot in in maximal plantarflexion. In CVT, a lateral view in maximal plantarflexion will show irreducibility of the midfoot on the hindfoot (Mckie and Radomisli 2010).

Oblique talus can be easily distinguished from CVT via radiographic evaluation. While the finding of the navicular dorsolateral subluxation on the talus in the standing position is a shared finding with CVT, this deformity immediately corrects with a radiograph taken in maximum plantarflexion.

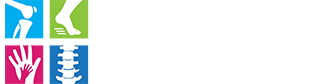

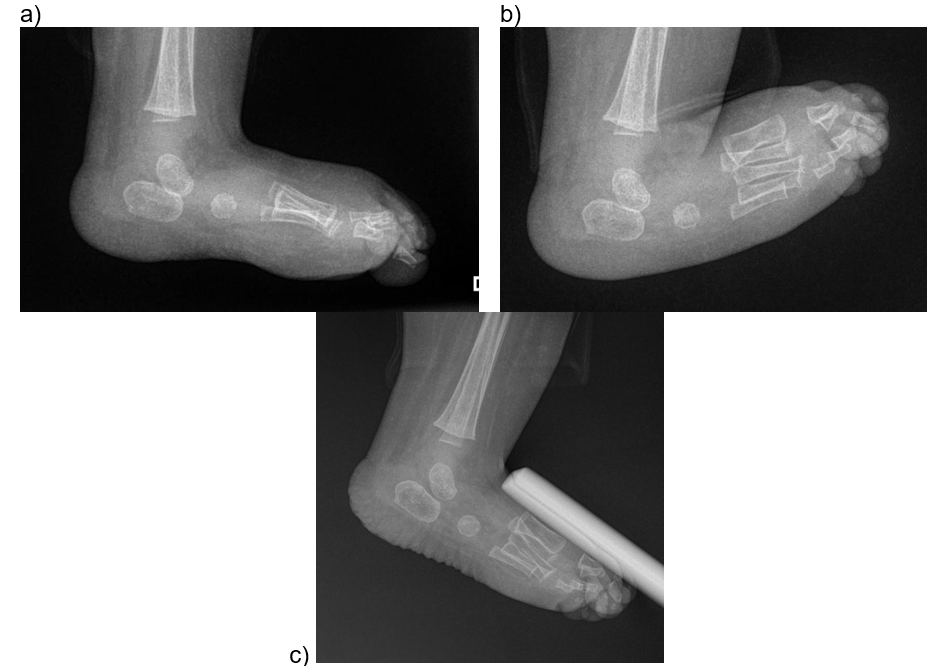

Figure 1a-c) Preoperative images of a patient with CVT. 1a) neutral resting position

Figure 1a-c) Preoperative images of a patient with CVT. 1a) neutral resting position1b) dorsiflexion view 1c) max and assisted plantarflexion view to rule out oblique talus.

Treatment:

In general, surgical correction is the mainstay of treatment. Traditionally, open surgical correction of vertical talus consisted first of reduction of the navicular on the talus via release of the tibialis anterior and capsular release, followed by pinning of the talonavicular joint and reconstruction of the spring ligament. Lengthening of the extensors and the peroneals and reduction of the calcaneocuboid joint was also performed, and correction of the equinus contracture achieved with Achilles tendon lengthening (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022). Complications, including wound necrosis, osteonecrosis, residual deformity, overcorrection, and the possibility of arthritis requiring salvage procedures (Herring, Mihran, and Tachdjian 2022; Miller and Dobbs 2015; Mckie and Radomisli 2010) were frequently described following open surgical correction of CVT. Due to this and the potential for a stiff post-surgical foot, a less invasive approach has been described.The newer approach, pioneered by Dobbs (Alaee, Boehm, and Dobbs 2007; Chan, Selvaratnam, and Garg 2016; Chalayon, Adams, and Dobbs 2012), consists of a series of weekly long-leg “reverse Ponseti” casts.

The talonavicular joint is gradually reduced as each cast and manipulation increases the foot adduction, plantarflexion, and hindfoot varus, essentially bringing the foot into a clubfoot position. Once reduction is achieved, the patient is taken to surgery. The talonavicular joint is pinned with a retrograde K-wire, with a small open reduction if the talonavicular joint is not fully reduced. Once the talonavicular joint is stabilized, the equinus contracture can be corrected with a percutaneous heelcord tenotomy. Lengthening of the peroneals and extensor tendons can be performed if there is residual abduction or extension. Post-operatively, the patient is placed into a long leg cast and eventually braced to maintain their correction. Five-year follow-up studies have shown excellent results in clinical appearance of the foot, function, and correction of deformity (Yang and Dobbs 2015; Dobbs et al. 2006).

Figure 2a-b) Postoperative images of a patient after reverse Ponseti casting and open talarnavicular pinning and achilles tenotomy.

Complications:

In addition to traditional surgical complications such as infection, wound necrosis and damage to nearby structures, surgical intervention of CVT has some unique risks. These include talar necrosis, joint stiffness, and undercorrection of the original deformity (Alaee, Boehm, and Dobbs 2007). The reduction of the talonavicular joint, step one in the technique, can be lost causing a recurrence of the of the CVT deformity. Improper casting techniques can result in an improper correction of the talus. Education on correct CVT casting is necessary for the success of the surgery. Complications can also result when a CVT is missed and/or left untreated. All of these complications can result in the patient needing multiple surgical procedures (Alaee, Boehm, and Dobbs 2007).Related Videos:

References:

- Alaee, Farhang, Stephanie Boehm, and Matthew B. Dobbs. 2007. “A New Approach to the Treatment of Congenital Vertical Talus.” Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics 1 (3): 165–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-007-0037-1.

- Aslani, Hossein, Ali Sadigi, Ali Tabrizi, Mohammadreza Bazavar, and Mehdi Mousavi. 2012. “Primary Outcomes of the Congenital Vertical Talus Correction Using the Dobbs Method of Serial Casting and Limited Surgery.” Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics 6 (4): 307–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-012-0433-z.

- Chalayon, Ornusa, Amelia Adams, and Matthew B. Dobbs. 2012. “Minimally Invasive Approach for the Treatment of Non-Isolated Congenital Vertical Talus.” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 94 (11): e73. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.K.00164.

- Chan, Yuen, Veenesh Selvaratnam, and Neeraj Garg. 2016. “A Comparison of the Dobbs Method for Correction of Idiopathic and Teratological Congenital Vertical Talus.” Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics 10 (2): 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-016-0727-7.

- Coleman, Sherman S., Frank H. Stelling, and Jerald Jarett. 1970. “Pathomechanics and Treatment of Congenital Vertical Talus.” Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research 70 (June): 62–72.

- Dobbs, Matthew B., Derek B. Purcell, Ryan Nunley, and Jose A. Morcuende. 2006. “Early Results of a New Method of Treatment for Idiopathic Congenital Vertical Talus.” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 88 (6): 1192–1200.

- Herring, John A., O Mihran, and Saunders Tachdjian. 2022. Tachdjian’s Pediatric Orthopaedics : From the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

- Mckie, Janay, and Timothy Radomisli. 2010. “Congenital Vertical Talus: A Review.” Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery, The Pediatric Pes Planovalgus Deformity, 27 (1): 145–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpm.2009.08.008.

- Merrill, Laura J., Christina A. Gurnett, Anne M. Connolly, Alan Pestronk, and Matthew B. Dobbs. 2011. “Skeletal Muscle Abnormalities and Genetic Factors Related to Vertical Talus.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 469 (4): 1167–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1475-5.

- Miller, Mark, and Matthew B. Dobbs. 2015. “Congenital Vertical Talus: Etiology and Management.” Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 23 (10): 604–11. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00034.

- Yang, Justin S., and Matthew B. Dobbs. 2015. “Treatment of Congenital Vertical Talus: Comparison of Minimally Invasive and Extensive Soft-Tissue Release Procedures at Minimum Five-Year Follow-Up.” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 97 (16): 1354–65.