Study Guide

Adolescent Hallux Valgus

Key Points:

- Initial evaluation should include identifying intrinsic and extrinsic causes

- More common in females than males and more commonly bilaterally. Unilateral cases should prompt further workup into etiology.

- Unlike adults, intra-articular pain and stiffness are rare

- Hallux Valgus Angle (HVA), Inter-Metatarsal Angle (IMA), and Distal Metatarsal Articular Angle (DMAA) are commonly measured on standing AP radiographs.

- Shoe wear modification and shoe wear fit assessment should be included in non-operative management

- Operative management should include soft tissue and bony correction to prevent high rates of recurrence.

Description:

Hallux valgus is the lateral deviation of the first metatarsal creating an apex of deformity at the first metatarsal-phalangeal joint and a prominence of the first metatarsal head medially at that apex. There are both intrinsic and extrinsic causes of hallux valgus. Intrinsic causes include a genetic predisposition, excessively long first metatarsal, metatarsus primus varus, and association with flat foot. Shoe wear, in particular shoes with a narrow toe box, is the most commonly cited extrinsic cause of hallux valgus.Epidemiology:

Although the true incidence of hallux valgus is unknown, it is known to be more common in females than males and is typically bilateral. Females often inherit the condition from their mothers. The true genetic heritability pattern is unknown, and may be multifactorial in nature. Cases of unilateral hallux valgus without family history should prompt evaluation for other causes of hallux valgus such as spinal cord anomalies, peripheral nerve lesions, or cerebral palsy.Clinical Findings:

Most pediatric and adolescent patients are asymptomatic or may only note mild pressure on the prominent medial metatarsal head with improperly fitting shoes. When pain is present, it is commonly located over the medial prominence of the first metatarsal head or at the site where the laterally deviated hallux overlaps the second toe. Unlike adult patients, intra-articular pain and stiffness is uncommon in pediatric and adolescent patients.Foot deformity and difficulty with shoe wear are common patient complaints. Discussion and evaluation of shoe choices and fit should be done. Overall lower extremity alignment including torsional profile should be examined. Increased external tibial torsion and genu valgum will contribute to the mechanical forces causing valgus at the first MTP joint. Screening for ligamentous laxity is important as a risk factor for recurrence of hallux valgus after surgical treatment. Pes planus is common in association with hallux valgus. Examination of Achilles tendon contractures and flexibility of the midfoot and hindfoot should be completed. Very young patients may have a deformity of the interphalangeal joint including a flexion contracture. In a case of painful hallux valgus, other sources of pain including arthritis or adjacent soft tissue or bone lesions should be excluded.

Imaging Studies:

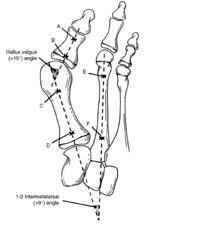

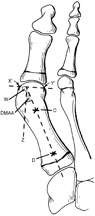

Standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of both feet should be taken to evaluate hallux valgus. The lateral radiograph should be evaluated for talo-calcaneal angle, calcaneal pitch (potential evidence of a tight Achilles tendon), Meary’s Angle (lateral talus-first metatarsal angle), and evidence of pes planus or flatfoot. Inspection for causes of pes planus, such as tarsal coalition, should be completed. On the AP radiograph, three commonly reported angles are shown in Figure 1. The inter-metatarsal angle (IMA) measures the angle between the first and second metatarsal shafts. This angle is typically less than 9 degrees. (Coughlan, 1999) The hallux valgus angle (HVA) measures the angle between the first metatarsal and the proximal phalanx. This angle should be less than 15 degrees. (Coughlan, 1999) The distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA) measures the angular relation between the shaft of the first metatarsal and its distal articular surface. (Figure 2). Additionally, evaluation of the metatarsal phalangeal joint for congruity and relative lengths of the first and second metatarsal should be completed. A congruous first metatarsal joint is much more common in adolescents than adults with hallux valgus. Figure 1

Figure 1  Figure 2

Figure 2Treatment:

Non-operative measures include night time bracing, day time splinting, physical therapy, and activity modification. The most important factor that can affect symptoms is shoe wear modification and assessment of shoe fit. Non-operative treatment is the mainstay of pediatric and adolescent hallux valgus treatment (Groiso, 1992).Practitioners must take care in evaluating specific patient complaints. Due to high complication and recurrence rates in pediatric and adolescent hallux valgus, surgical intervention for pure cosmetic reasons related to the deformity itself should be avoided. Surgical intervention is reserved for unrelenting pain despite non-operative measures of activity and shoe wear modification in a near to fully skeletally mature patient.

Surgical intervention consists of distal soft tissue realignment (McBride), osteotomy, and attention to the DMAA. Soft tissue realignment alone should never be performed in adolescents given high recurrence rates. Osteotomy can be performed in the distal or proximal metatarsal or medial cuneiform. There are general guidelines to help determine the location of the osteotomy. Hallux valgus with a congruent MTP joint can be corrected with a distal Mitchell or chevron type osteotomy. A non-congruent joint or significant metatarsus primus varus is corrected with a proximal metatarsal osteotomy or medial cuneiform osteotomy. Although double level osteotomies are commonly performed (Peterson, 1993) care should be taken as overcorrection can occur (Edmonds, 2015). Guided growth techniques are being investigated although, a large series with adequate follow-up is lacking (Davids, 2007; Greene, 2015).

Complications:

Recurrence and continued deformity, including over correction, are the most common complications with surgical intervention. Complication rates approach one in six to seven patients in most studies and also include infection and avascular necrosis (Edmonds, 2015; Johnson, 2004).Related Videos:

References:

- Chell J, Dhar S. Pediatric Hallux Valgus. Foot Ankle Clin N Am. 2014 (19):235-243

- Coughlin M, Mann R, eds. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle. 7th ed. St Louis MO; Mosby, 1999:270

- Davids JR, McBrayer D, Blackhurst DW. Juvenile hallux valgus deformity: surgical management by lateral hemiepiphyseodesis of the great toe metatarsal. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007 27: 826-830.

- Edmonds EW, Ek D, Bomar JD, et al. Preliminary radiographic outcomes of surgical correction in Juvenile Hallux Valgus: single proximal, single distal versus double osteotomies. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015 (35): 307-313

- Greene JD, Nicholson AD, Sanders JO, et al. Analysis of serial radiographs of the foot to determine normative values for the growth of the first metatarsal to guide hemiepiphysiodesis for immature hallux valgus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015, epub ahead of print.

- Groiso JA. Juvenile hallux valgus: A conservative approach to treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992(74): 1367-1374

- Johnson AE, Georgopoulos G, Erickson MA, et al. Treatment of adolescent hallux valgus with the first metatarsal double osteotomy: the Denver experience. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004 (24): 358-362

- Perterson HA, Newman SR. Adolescent bunion deformity treated with double osteotomy and longitudinal pin fixation of the first ray. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993 (13): 80-84.