Study Guide

Adolescent Acetabular Dysplasia (Idiopathic DDH)

Key Points:

- Acetabular dysplasia is estimated at a 3-5% prevalence

- Acetabular dysplasia may develop throughout childhood or later in adolescence

- Plays a leading role in the development of hip osteoarthritis

- Periacetabular osteotomy is an effective treatment that can alter the natural history of dysplastic hips

Description:

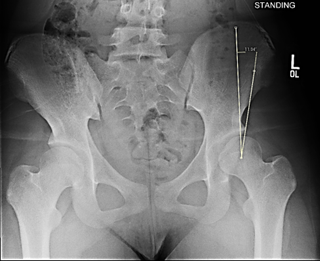

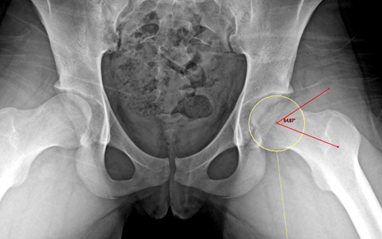

Acetabular dysplasia is a spectrum of hip disease characterized by abnormal acetabular morphology which can lead to pain secondary to aberrant hip mechanics. Acetabular dysplasia typically refers to a shallow acetabulum that does not adequately cover the femoral head, which leads to mechanical issues including instability, impingement, and muscular overload as the surrounding musculature attempts to stabilize the hip. Further structural damage to the femoral head, acetabulum, labrum, and surrounding anatomy can occur because of abnormal joint mechanics. Acetabular dysplasia is traditionally classified by the lateral center edge angle of Wiberg (LCEA) with hips <20 as dysplastic, between 20-25 as borderline, and >25 as normal.(Wiberg 1939, Wiberg 1939) It is now recognized that acetabular dysplasia cannot be fully described by LCEA alone and several other radiographic features are used to diagnose dysplasia. (McClincy, Wylie et al. 2019) There can be global or focal acetabular dysplasia based on the pattern and location of bony deficiency(Nepple, Wells et al. 2017) .Although lateral deficiency is commonly present in hip dysplasia by definition of the LCEA, anterosuperior deficiency, global and posterosuperior deficiency are all seen within the spectrum of hip dysplasia (Nepple, Wells et al. 2017). This can be residual from treatment from childhood developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) or newly discovered in teenage or early adulthood(Liporace, Ong et al. 2003, Lee, Mata-Fink et al. 2013). Acetabular dysplasia is a leading cause of the development of hip osteoarthritis(Murphy, Ganz et al. 1995, Jacobsen and Sonne-Holm 2005, Reijman, Hazes et al. 2005). Figure 1. Lateral Center Edge Angle of Wiberg as measured from the center of the femoral head, perpendicular to the axis of the body.

Figure 1. Lateral Center Edge Angle of Wiberg as measured from the center of the femoral head, perpendicular to the axis of the body.

Epidemiology:

The true prevalence of hip dysplasia is unknown but has been estimated to be 3-5% in the general population(Gosvig, Jacobsen et al. 2010, Engesæter, Laborie et al. 2013). Acetabular dysplasia is more common in females than males. Adolescent or young adult hip dysplasia is still predominantly found in females, but less so than DDH(Lee, Mata-Fink et al. 2013). There is a strong familial component to acetabular dysplasia, and about 50% of patients diagnosed with hip dysplasia have a family history of hip disease(Lee, Mata-Fink et al. 2013).Clinical Findings:

Patients with acetabular dysplasia often complain of groin pain, though lateral hip pain or posterior hip pain from abnormal joint mechanics can also occur(Nunley, Prather et al. 2011). Patients typically describe hip pain that is worse with standing or sitting for too long. They may complain of symptoms consistent with abductor fatigue or limp at the end of the day(Nunley, Prather et al. 2011). In cases of anterior instability, they may have pain walking in high heels, going downstairs, or in other activities that place their hip in extension.On exam, patients may have an increased range of motion, including increased internal rotation and hip flexion. Popping or clicking is common and may be secondary to internal or external coxa saltans. Joint laxity may be present and a Beighton’s score or Hakim-Grahame questionnaire should be conducted (Santore, Gosey et al. 2020). Hip capsule integrity and tension can be tested by examining the patient supine with both legs extended at rest. Capsule laxity is indicated by an increased external rotation of one side compared to the other at rest. Hip instability tests may also be positive with reproducible pain when placing the hip in extension and/or external rotation. The prone apprehension relocation test (PART) can also indicate anterior under coverage and instability if positive (Spiker, Fabricant et al. 2020).

Intra- and extra-articular hip impingement may also exist in the setting of hip dysplasia and microinstability. Intra-articular hip impingement can also be present with hip instability and flexion, adduction, and internal rotation may cause pain (Nunley, Prather et al. 2011). Associated pain with pure flexion can be secondary to anterior inferior iliac spine impingement. Posterior or trochanteric extra-articular impingement may present with pain laterally or posteriorly in positions of hip abduction, extension and external rotation.

Observing the patient’s gait pattern may reveal in-toeing, wide-based stance, limp, or positive Trendelenberg.

Imaging Studies:

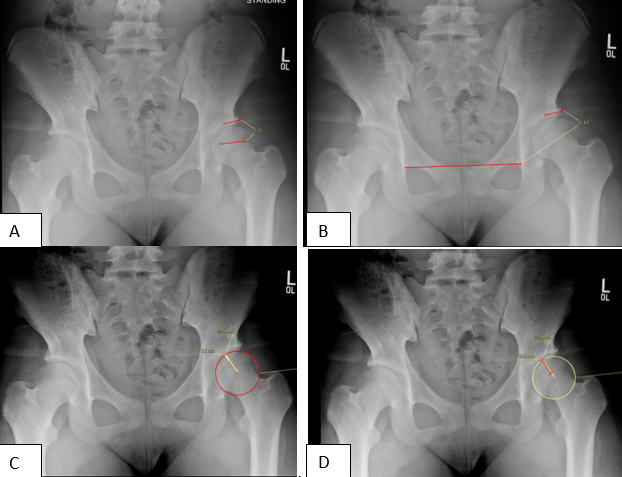

Plain radiographs including a standing AP pelvis, false profile views, and modified Dunn should all be obtained (Clohisy, Carlisle et al. 2008, Tachibana, Fujii et al. 2019). On the AP pelvis radiograph, lateral center edge angle of Wiberg, the Tönnis angle, FEAR index, the anterior and posterior wall indices, and signs of acetabular retroversion such as the ischial spin sign, posterior wall sign, and crossover sign, can help further characterize the acetabular dysplasia (Figure 2)(Wiberg 1939, Tonnis 1987, Siebenrock, Kistler et al. 2012, Wyatt, Weidner et al. 2017).

Figure 2 (above). A. FEAR Index. B. Tonnis Angle. C Anterior Wall Index. D. Posterior Wall Index

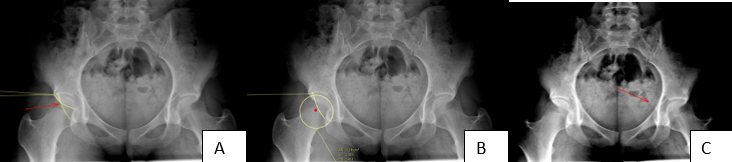

Figure 3. Signs of Acetabular Retroversion. A. Cross over Sign B. Posterior wall Sign C. Ischial Spine Sign

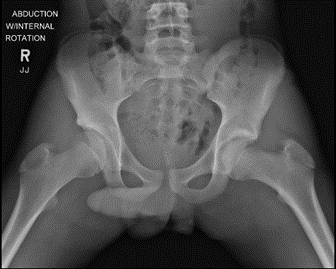

The anterior center edge angle can be measured on the false-profile view, and the Dunn and modified Dunn views can show femoral asphericity or decreased head-neck offset. An abduction-internal rotation view (Von Rosen) is often examined for hip congruency during the surgical decision making process.

Figure 4. A (left). Upright false profile radiograph with anterior center edge angle. B (middle). 45 degree Dunn view (modified Dunn) with alpha angle. C (right). Abduction and internal rotation view (Von Rosen).

Computed tomography can and is often used for further characterization of the acetabular dysplasia as well as contributing acetabular or femoral version abnormalities.

MRI is also useful in both the evaluation of hip dysplasia as well as the appropriateness of hip preservation surgery. MRI can help identify labral pathology, the status of the articular cartilage, other concomitant lesions or stress fractures, and surrounding tendon pathology.

Treatment:

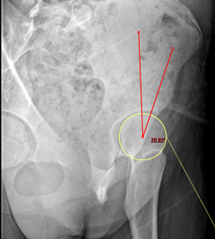

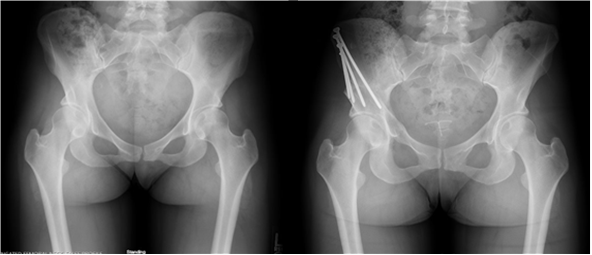

Treatment of acetabular dysplasia varies with the severity, patient’s age, physical limitations, and the extent to which it affects their quality of life. There is evidence that treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia (LCE <15) in hips with intact articular cartilage with acetabular reorientation can affect the natural history of hip dysplasia and prolong the longevity of the native hip.(Murphy, Ganz et al. 1995, Lerch, Steppacher et al. 2017, Wyles, Vargas et al. 2020)The mainstay of treatment for hip instability secondary to acetabular dysplasia in the skeletally mature patient is the periacetabular osteotomy, as developed by Ganz.(Ganz, Klaue et al. 1988)

The first line treatment of acetabular dysplasia in moderate and mild cases is physical therapy, consisting of core, back and hip strengthening. Although neither acetabular bony deficiency nor ligamentous factors can be improved by physical therapy, muscular strengthening can decrease symptoms from hip dysplasia by acting as secondary stabilizers around the hip. Activity modification for individuals experiencing hip pain solely during certain activities can also be recommended as an option.

Hip injections can be helpful for symptoms relating to labral pathology, but do not address underlying bony deficiencies. They are often utilized in a diagnostic fashion in order to differentiate between intra-articular and extra-articular causes of pain, as well as to provide temporary symptom relief.

Other hip and back conditions frequently can be seen simultaneously with hip dysplasia, including femoracetabular impingement, as well as other extra-articular hip impingent conditions, such as ischiofemoral impingement, femoral version abnormalities, lumbar spondylosis, external or internal snapping hip, and muscular tendinopathies around the hip (psoas, rectus, gluteus), which may all require separate treatment.

Figure 5 (above). Pre- and post-operative periacetabular osteotomy for hip dysplasia.

Complications:

Periacetabular osteotomy is a technically complex procedure with a steep learning curve. Complications after periacetabular osteotomy include deep venous thrombosis, nerve palsy including damage to the sciatic nerve, intra-articular propagation of the osteotomy site, and osteotomy nonunion. Failure of fixation including hardware migration, osteotomy displacement, and deep or superficial wound infections can also occur.Related Videos:

References:

- Clohisy, J. C., J. C. Carlisle, P. E. Beaulé, Y. J. Kim, R. T. Trousdale, R. J. Sierra, M. Leunig, P. L. Schoenecker and M. B. Millis (2008). "A systematic approach to the plain radiographic evaluation of the young adult hip." J Bone Joint Surg Am 90 Suppl 4(Suppl 4): 47-66.

- Engesæter, I., L. B. Laborie, T. G. Lehmann, J. M. Fevang, S. A. Lie, L. B. Engesæter and K. Rosendahl (2013). "Prevalence of radiographic findings associated with hip dysplasia in a population-based cohort of 2081 19-year-old Norwegians." Bone Joint J 95-b(2): 279-285.

- Ganz, R., K. Klaue, T. S. Vinh and J. W. Mast (1988). "A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results." Clin Orthop Relat Res(232): 26-36.

- Gosvig, K. K., S. Jacobsen, S. Sonne-Holm, H. Palm and A. Troelsen (2010). "Prevalence of Malformations of the Hip Joint and Their Relationship to Sex, Groin Pain, and Risk of Osteoarthritis: A Population-Based Survey." JBJS 92(5): 1162-1169.

- Jacobsen, S. and S. Sonne-Holm (2005). "Hip dysplasia: a significant risk factor for the development of hip osteoarthritis. A cross-sectional survey." Rheumatology (Oxford) 44(2): 211-218.

- Lee, C. B., A. Mata-Fink, M. B. Millis and Y. J. Kim (2013). "Demographic differences in adolescent-diagnosed and adult-diagnosed acetabular dysplasia compared with infantile developmental dysplasia of the hip." J Pediatr Orthop 33(2): 107-111.

- Lerch, T. D., S. D. Steppacher, E. F. Liechti, M. Tannast and K. A. Siebenrock (2017). "One-third of Hips After Periacetabular Osteotomy Survive 30 Years With Good Clinical Results, No Progression of Arthritis, or Conversion to THA." Clin Orthop Relat Res 475(4): 1154-1168.

- Liporace, F. A., B. Ong, A. Mohaideen, A. Ong and K. J. Koval (2003). "Development and injury of the triradiate cartilage with its effects on acetabular development: review of the literature." J Trauma 54(6): 1245-1249.

- McClincy, M. P., J. D. Wylie, Y. J. Kim, M. B. Millis and E. N. Novais (2019). "Periacetabular Osteotomy Improves Pain and Function in Patients With Lateral Center-edge Angle Between 18° and 25°, but Are These Hips Really Borderline Dysplastic?" Clin Orthop Relat Res 477(5): 1145-1153.

- Murphy, S. B., R. Ganz and M. E. Müller (1995). "The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome." J Bone Joint Surg Am 77(7): 985-989.

- Nepple, J. J., J. Wells, J. R. Ross, A. Bedi, P. L. Schoenecker and J. C. Clohisy (2017). "Three Patterns of Acetabular Deficiency Are Common in Young Adult Patients With Acetabular Dysplasia." Clin Orthop Relat Res 475(4): 1037-1044.

- Nunley, R. M., H. Prather, D. Hunt, P. L. Schoenecker and J. C. Clohisy (2011). "Clinical presentation of symptomatic acetabular dysplasia in skeletally mature patients." J Bone Joint Surg Am 93 Suppl 2: 17-21.

- Reijman, M., J. M. Hazes, H. A. Pols, B. W. Koes and S. M. Bierma-Zeinstra (2005). "Acetabular dysplasia predicts incident osteoarthritis of the hip: the Rotterdam study." Arthritis Rheum 52(3): 787-793.

- Santore, R. F., G. M. Gosey, M. P. Muldoon, A. A. Long and R. M. Healey (2020). "Hypermobility Assessment in 1,004 Adult Patients Presenting with Hip Pain: Correlation with Diagnoses and Demographics." J Bone Joint Surg Am 102(Suppl 2): 27-33.

- Siebenrock, K. A., L. Kistler, J. M. Schwab, L. Büchler and M. Tannast (2012). "The acetabular wall index for assessing anteroposterior femoral head coverage in symptomatic patients." Clin Orthop Relat Res 470(12): 3355-3360.

- Spiker, A. M., P. D. Fabricant, A. C. Wong, J. R. Suryavanshi and E. L. Sink (2020). "Radiographic and clinical characteristics associated with a positive PART (Prone Apprehension Relocation Test): a new provocative exam to elicit hip instability." J Hip Preserv Surg 7(2): 288-297.

- Tachibana, T., M. Fujii, K. Kitamura, T. Nakamura and Y. Nakashima (2019). "Does Acetabular Coverage Vary Between the Supine and Standing Positions in Patients with Hip Dysplasia?" Clin Orthop Relat Res 477(11): 2455-2466.

- Tonnis, D. (1987). "Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults. ." Berlin Springer.

- Tönnis, D. and W. Remus (2004). "Development of hip dysplasia in puberty due to delayed ossification of femoral nucleus, growth plate and triradiate cartilage." J Pediatr Orthop B 13(5): 287-292.

- Wiberg, G. (1939). "The anatomy and roentgenographic appearance of a normal hip joint." Acta Chir Scand: 7-38.

- Wiberg, G. (1939). "Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint: with special reference to the complication of osteoarthritis." Acta Chir Scand 83: 1-135.

- Wyatt, M., J. Weidner, D. Pfluger and M. Beck (2017). "The Femoro-Epiphyseal Acetabular Roof (FEAR) Index: A New Measurement Associated With Instability in Borderline Hip Dysplasia?" Clin Orthop Relat Res 475(3): 861-869.

- Wyles, C. C., J. S. Vargas, M. J. Heidenreich, K. C. Mara, C. L. Peters, J. C. Clohisy, R. T. Trousdale and R. J. Sierra (2020). "Hitting the Target: Natural History of the Hip Based on Achieving an Acetabular Safe Zone Following Periacetabular Osteotomy." JBJS 102(19): 1734-1740.